Word alignment is an important task, and used to be a key component of statistical machine translation (SMT). Although word alignment is no longer explicitly modeled in neural machine translation (NMT), it still plays an important role in NMT model analysis, lexically constrained decoding and automatic post-editing.

The attention mechanism, which is now widely used in various AI tasks, was motivated by the need to align source words with target words in machine translation. In recent years, however, it has been found that the attention in NMT models does not match word alignments as expected, especially in Transformer models. This is because the NMT models compute the cross-attention between source and target with only part of the target context, which inevitably brings noisy alignments when the prediction is ambiguous. To get better word alignments, additional alignment labels are required to guide the training process.

In our recent ACL 2021 paper, we propose a self-supervised word alignment model called Mask-Align. Unlike NMT-based aligners, Mask-Align parallelly masks out each target token and recovers it conditioned on the source and other target tokens. This will take full advantage of bidirectional context on the target side, and reduce alignment errors caused by wrong predictions.

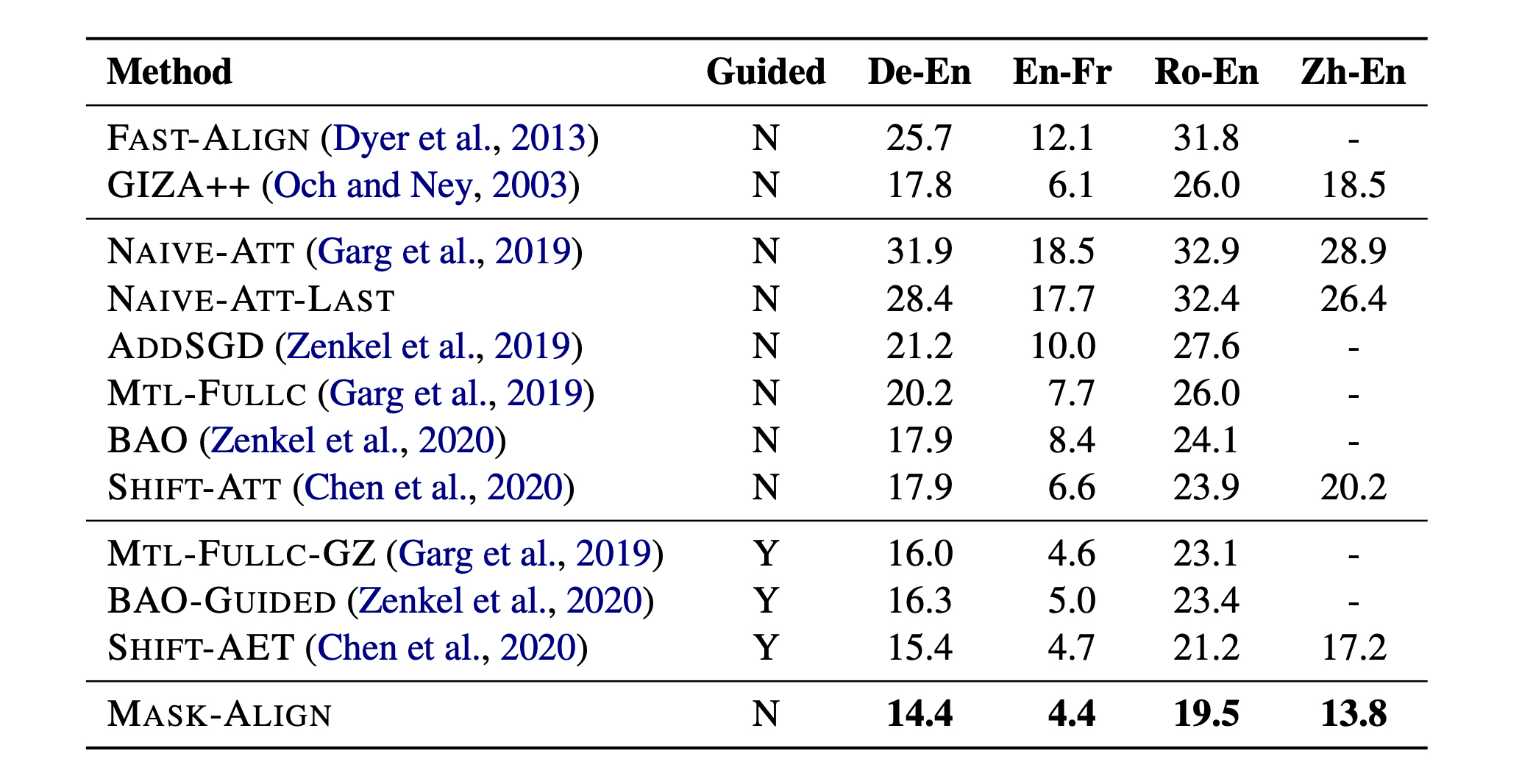

Our model achieves state-of-the-art word alignment results on four language pairs, improving performance over GIZA++ by 1.7-6.5 AER points. You can find the code here.

Problem with NMT-based Aligners

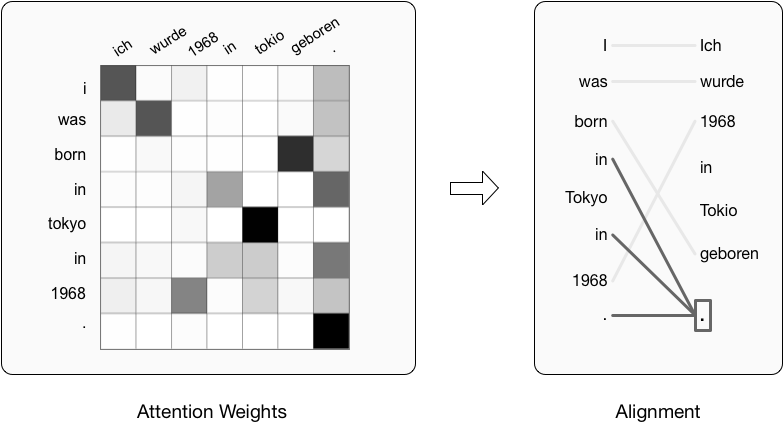

Here is an illustration of inducing alignments from an NMT-based aligner. The model predicts each target token conditioned on the source and previous target tokens and generates alignments from the attention weights between source and target. When predicting “Tokyo”, it wrongly generates “1968” because future context is not observed. Consequently, the target token “Tokyo” is aligned to the source token “1968”.

Intuitively, this error would not have occurred if the model had observed “1968” in the future target context. Inspired by this, we propose our method, Mask-Align.

Mask-Align

Mask-Align masks out each target token and recovers it conditioned on the source and the full target context. Therefore, when predicting the masked token “Tokyo”, our model will not generate “1968” because in that case there will be two “1968”s in the target sentence, and the resulting alignment links are correct as we expect.

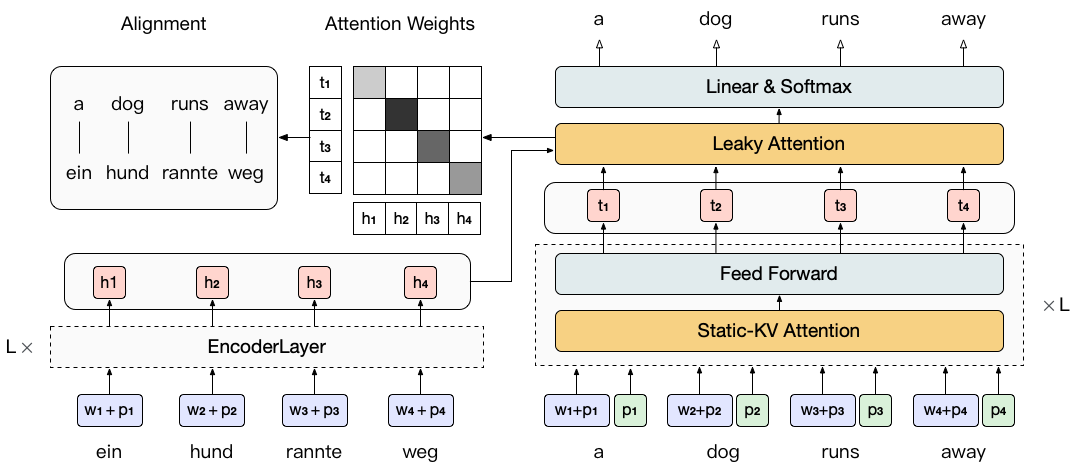

The above idea is simple but not trivial to implement. As self-attention is fully-connected, we can only mask out and repredict one target token at a time with a vanilla Transformer. For a target sentence of length N, this requires N seperate forward passes. To make this process more efficient, inspired by DisCo [1], we propose to use static-KV attention to mask out and predict all target tokens in parallel in a single forward pass.

Static-KV attention differs from conventional self-attention in two ways. First, it initializes the representation of each token with its position embedding, which equals to masking out this token. Second, it keeps the key and value vectors of each token unchanged from the sum of token and position embeddings, and masks out the attention connection for each token from its own embeddings (depicted as -x->). These changes allow us to compute representations in parallel with all tokens masked individually and avoid model degradation due to information leakage.

We also remove the cross-attention in all but the last decoder layer. This makes the interaction between the source and target restricted in the last layer. Our experiments demonstrate that this modification improves alignment results with fewer model parameters. The overall architecture of Mask-Align is shown in the figure below.

Leaky Attention

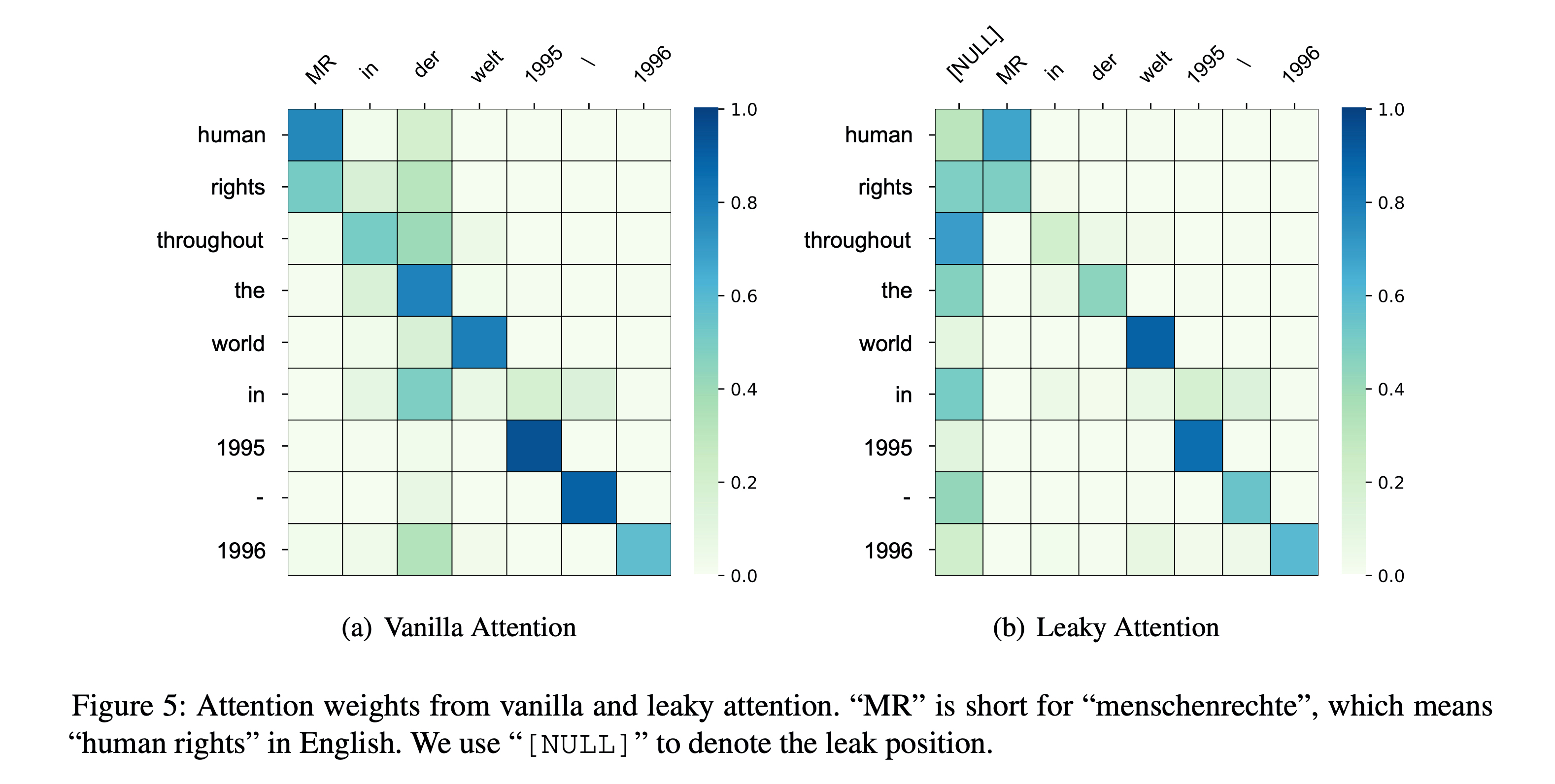

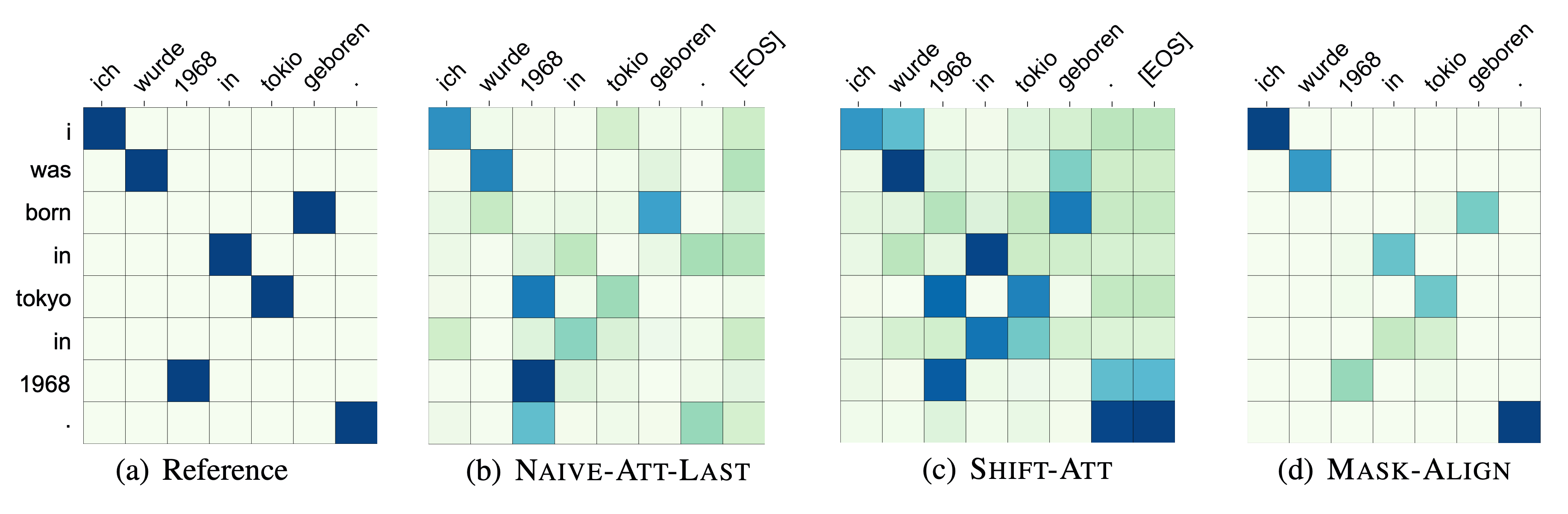

Extracting alignments from vanilla cross-attention often suffers from the high attention weights on some specific source tokens such as periods, [EOS], or other high frequency tokens, which are similar to the “garbage collectors” in statistical aligners. Here is an example where the source token "." is the collector. As a result, two "in"s are wrongly aligned to it.

We conjecture that this phenomenon is due to the incapability of NMT-based aligners to deal with tokens that have no counterparts on the other side because there is no empty (NULL) token that is widely used in statistical aligners. So these collectors essentially play the role of the NULL token. Obviously, this phenomenon is detrimental if we want to obtain high quality alignments from the attention weights.

We propose to explicitly model the NULL token with an attention variant, namely leaky attention. When calculating cross-attention weights, leaky attention provides an extra “leak” position in addition to the encoder outputs. To be specific, we parameterize the key and value vectors as \(\mathbf{k_{NULL}}\) and \(\mathbf{v_{NULL}}\) for the leak position in the cross-attention, and concatenate them with the transformed vectors of the encoder outputs \(\mathbf{H}_{\text{enc}}\):

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{z}_{i} &= \mathrm{Attention}(\mathbf{h}_{i}^{L}\mathbf{W}^{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) \\ % \mathbf{K} &= [\mathbf{k}_{\text{NULL}}; \mathbf{H}_{\text{enc}}\mathbf{W}^{K}] \\ % \mathbf{V} &= [\mathbf{v}_{\text{NULL}}; \mathbf{H}_{\text{enc}}\mathbf{W}^{V}] \mathbf{K} &= \mathrm{Concat}(\mathbf{k}_{\text{NULL}}, \mathbf{H}_{\text{enc}}\mathbf{W}^{K}) \\ \mathbf{V} &= \mathrm{Concat}(\mathbf{v}_{\text{NULL}}, \mathbf{H}_{\text{enc}}\mathbf{W}^{V}) \end{aligned}\]The figures below show that leaky attention can alleviate the collector phenomenon in the attention weights, leading to more accurate word alignments.

Agreement

To better utilize the attention weights from both directions, we encourage agreement between them both in training and inference to improve the symmetry of the model in both training and inference, which has proved effective in statistical alignment models [2]. During training, we introduce the an agreement loss:

\[\mathcal{L}_{a} = \mathrm{MSE}\left(\boldsymbol{W}_{\mathbf{x\rightarrow{y}}}, \boldsymbol{W}_{\mathbf{y\rightarrow{x}}}^{\top}\right)\]to encourage the models in two directions to generate similar attention weight matrices. Due to the introduction of leaky attention, we only consider the renormalized weights at positions other than the leak position.

During inference, we compute the alignment score \(S_{ij}\) between the j-th source token and the i-th target token as the harmonic mean of attention weights \(W_{\mathbf{x\rightarrow{y}}}^{ij}\) and \(W_{\mathbf{y\rightarrow{x}}}^{ji}\) from two directional models:

\[S_{ij} = \frac{2\,W_{\mathbf{x\rightarrow{y}}}^{ij}\,W^{ji}_{\mathbf{y\rightarrow{x}}}}{W_{\mathbf{x\rightarrow{y}}}^{ij}+W^{ji}_{\mathbf{y\rightarrow{x}}}}\]We found in our experiments that this method of extracting alignment results works better than the traditionally used grow diagonal heuristic [3].

Results

The following table shows the comparison between Mask-Align and other unsupervised statistical and neural aligners. As we can see, Mask-Align achieves the best results on all the four language pairs.

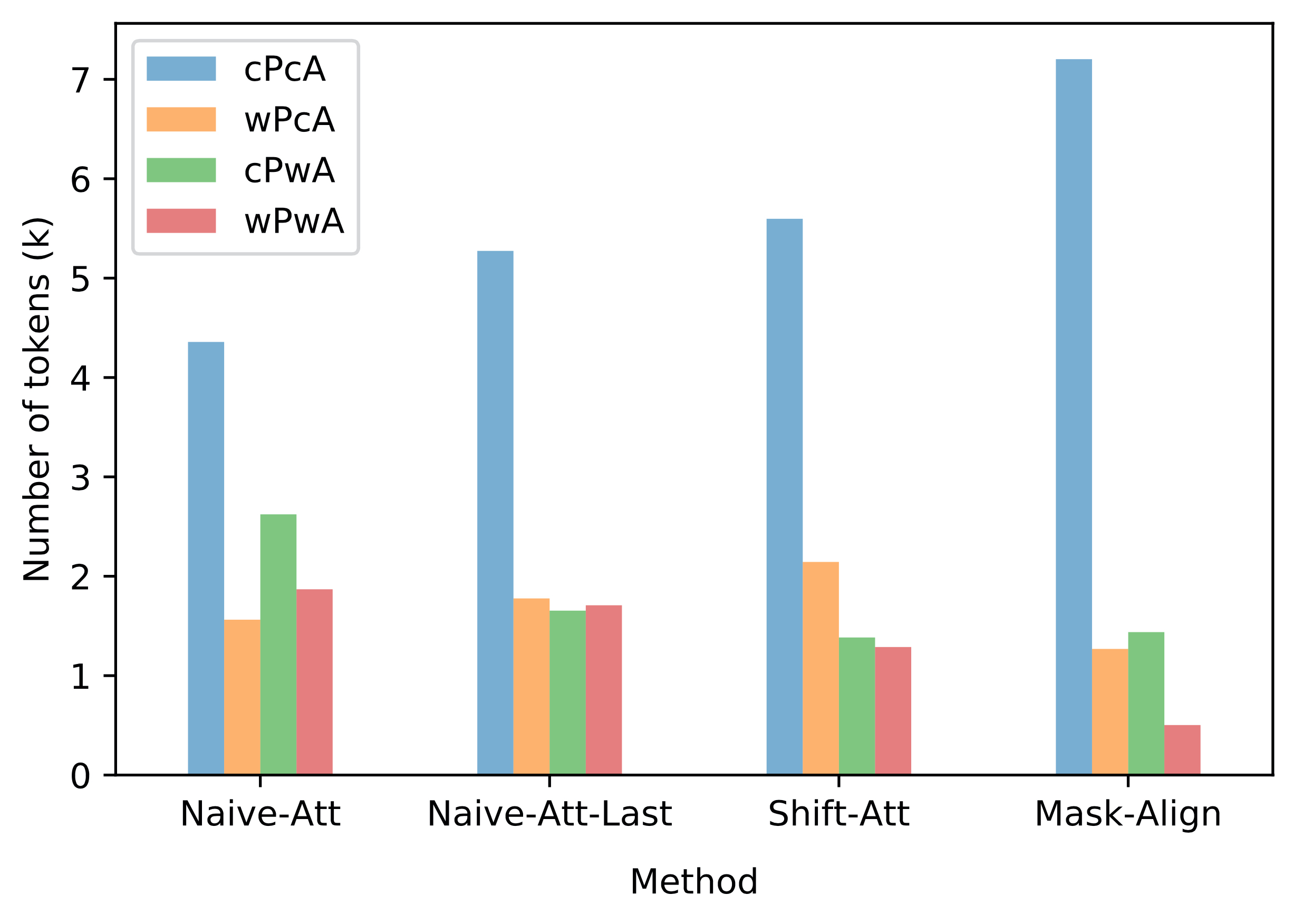

We further analyzed the relevance between the correctness of word-level prediction and alignment. In the following figure, we can see that Mask-Align significantly reduces the alignment errors caused by the prediction errors (wrong Prediction & wrong Alignment, wPwA) compared to other NMT-based aligners.

Also, the attention weights obtained by Mask-Align is more consistent with the word alignment reference than other methods.

What’s Next ?

In the future, we plan to extend our method to directly generate symmetrized alignments without leveraging the agreement between two unidirectional models. For further discussion, please contact: Chi Chen (chenchi19@mails.tsinghua.edu.cn).

References

[1] Jungo Kasai, James Cross, Marjan Ghazvininejad, and Jiatao Gu. 2020. Non-autoregressive machine translation with disentangled context transformer. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 5144–5155. PMLR.

[2] Percy Liang, Ben Taskar, and Dan Klein. 2006. Alignment by agreement. In Proceedings of the Human Language Technology Conference of the NAACL, Main Conference, pages 104–111.

[3] Philipp Koehn, Amittai Axelrod, Alexandra Birch Mayne, Chris Callison-Burch, Miles Osborne, and David Talbot. 2005. Edinburgh system description for the 2005 IWSLT speech translation evaluation. In International Workshop on Spoken Language Translation (IWSLT) 2005.